By Tom McGowan

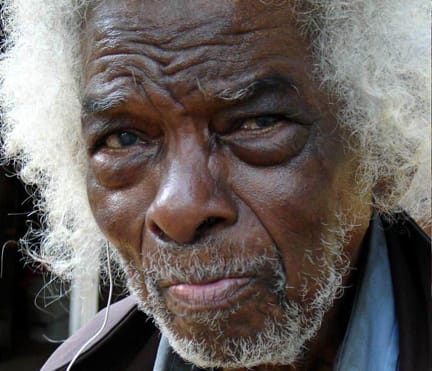

He stood 6′ tall and weighed 190 pounds, had a majestic afro of white hair which glowed in the sun like a halo, and was part American Indian and the rest African American.

He had bought an old house for next to nothing back when the neighborhood was in rough shape. He took it apart and put it back together. New foundation, cut a room off, added one on the back. He was a man of many skills — construction only being one of them — and had every tool known to man — not just one of them — typically two or three. And his tools were like his children. He had trouble loaning them out and worried, about worried to death, until they came back to him. Never could give one away.

His paranoia worsened over the years. He would tell me repeatedly about his missing brass-bound mason’s level. Four feet of beautiful wood and brass, that cost two or three weeks of wages back when he got it. Something to protect. And I heard for months that somebody had taken it from him. I went in his house and as I walked by his refrigerator, saw something in a little space between it and the wall. I said Marshall, come here, is this the level you were looking for? His reply: My god, they put it back! Yes, he got me fair and square on that one; I had no reply. I sometimes wonder if he made up the tool-loss stories to give him something to talk about, to have someone else share his worries.

Even at the age of 94 his constitution was strong and he rode a bicycle and would get up on a 24-foot extension ladder. He couldn’t work all day, but enjoyed taking things apart. His weakness was with fit and finish. While he reframed his house, he never got to the siding. He stopped at blackboard Temple brand sheathing. It was made of pressed wood, and after 30 years, it was turning back to sawdust. His back roof was leaking big time. I’d tried to patch it, but it needed a tear off and deck replacement; he—and the house—were just losing ground.

I would check on him each week on Saturday morning. At the door he would say “What do you want?” I would reply, “Just checking on you.” And then he would start talking, and since he lived alone and had no one to talk to, he wanted to talk my ear off. After a half hour I would find a way to ease out and get on with my Saturday chores.

Part of his paranoia caused him to cast off his friends, after two years or 20, he suddenly declared they were stealing from him. I had my ups and downs with Marshall myself, but I persisted and was back in moderately good graces with him after we hit some low points.

Come one hot July Fourth weekend, I went to check on him and he was not there. So I called Grady Hospital which is where he would be if he was in a jam. He had been there twice when he cut his hand up with his skill saw and later with his table saw. He had seven good fingers left after they patched him up over the years.

Indeed, he was at Grady. He had gone down to see an eye doctor and they kind of bagged him and kept him, like a butterfly in a net. Perhaps he had a heart problem that he never told me about. I don’t know. Or perhaps Grady needed to fill some beds.

The aide who was minding him, likely getting paid minimum wage, just rolled her eyes when I asked Marshall, “When are you going home?” She couldn’t say anything but it was plain he was not just going home. The social worker wouldn’t tell me squat due to HIPAA rules. I finally figured out they were sending him to a nursing home. I didn’t have any authority or paperwork to do anything for him; due to his paranoia, no one had authority to help him out. He was very, very independent.

One day I went to visit him at Grady and he had disappeared. It took a lot of work but I tracked him down to a skilled care home right across from the old firehouse at Boulevard and Auburn Avenue. I visited him every three or four days there. Initially, he was OK, and we would walk the hallways, but he refused to walk out in the neighborhood. It was obvious that they had him on medication; he shared a room with two other men and they all sat around, nodding off like zombies. He deteriorated over the next three weeks, and one Saturday morning while he was talking to me, he could only open one eye from time to time to look at me. The following Monday I got the call that he had died. The social worker there was more open then. I asked what happened, how did he end up here? “Well, Adult Protective Services took over,” she said. “On what basis did they take over his life?” I asked. It was self-neglect. “Why?” They drove by his house and looked at it. She asked how it was on the inside. Having street smarts, I declined to talk about that, as the inside was even worse than outside.

After he died, she gave his house keys to Marshall’s “current” friend who hadn’t yet been blacklisted by Marshall’s paranoia. I saw the man and his friend over there taking all sorts of stuff out of the house and I got worried. I knew Marshall had family— two daughters by marriage. He had been estranged from them for 25 years and we had no knowledge of their whereabouts. In addition, another man would show up once in a while. It was supposed to be his son but if I said that to Marshall, he would say firmly, “He’s not my son.” I called up Marshall’s “Not my son” to tell him what all was going on. I told him Marshall’s current friend said it was OK by “Not My Son” for him to handle things and “Not My Son” said he did not tell him that. So I got all three of us on the phone together and things reached sort of a stalemate. His current friend did file with the state to try to do something on legal issues. But what I was worried that the house might get emptied of all of his earthly goods and be left to rot and ruin. So I asked “Not My Son” to take a DNA test. I have to say the city morgue was very cooperative; the chief there kept the body in the cooler and would not let anyone bury or cremate him until we were done. In two or three weeks the results came back, and I called “Not My Son” and said “You know I got that sheet here from the DNA company. It has a lot of numbers and stuff on it but the last sentence I need to read you says there’s a 99.9% chance that you’re related to Marshall Milner.” There was a long pause. “Not My Son” is a big man and I heard him let out a big sigh. So after 67 years of being lied to and denied, denied and denied some more, it was finally confirmed that Marshall was his dad, period.

“Not My Son” took over managing the estate, and Marshall’s current friend graciously let him take over. We had a service for Marshall where friends and family came and got to say a few words. He was buried at Westview cemetery. At the last minute, I talked the undertaker into letting me slip my Swiss Army knife into Marshall’s casket; he was a tool man and I figured he needed that to take with him and to the next world. I thought Marshall would’ve appreciated that gesture. A contact of mine at the interment supplied me with a phone number for one of the half-sisters.

“Not My Son” labored long and hard to clean the house out and sold it. Late in the process I remember seeing him there with his two half-sisters, reunited after all these years. Talking about growing up in the Old Fourth Ward. Talking and laughing and going through old photos and how peculiar Marshall could be as a dad and how they had all ended up there after all this time. They managed to get some money out of the house, and a builder saved some of it and cut some of it loose and rebuilt it as a two-story home and sold it to a good family. So everybody came out well in the end. It wasn’t perfect, God knows. I remember when there was an undertaker who was holding Marshall’s body hostage, charging as much per day as a Holiday Inn Express. So there were peaks and valleys along the way. The high point was when “Not My Son” and his wife told me I was family, yes, I was family. And looking back, if it wasn’t perfect, well at least 99.9% of it was done right for Marshall and his folks

Comments are closed.